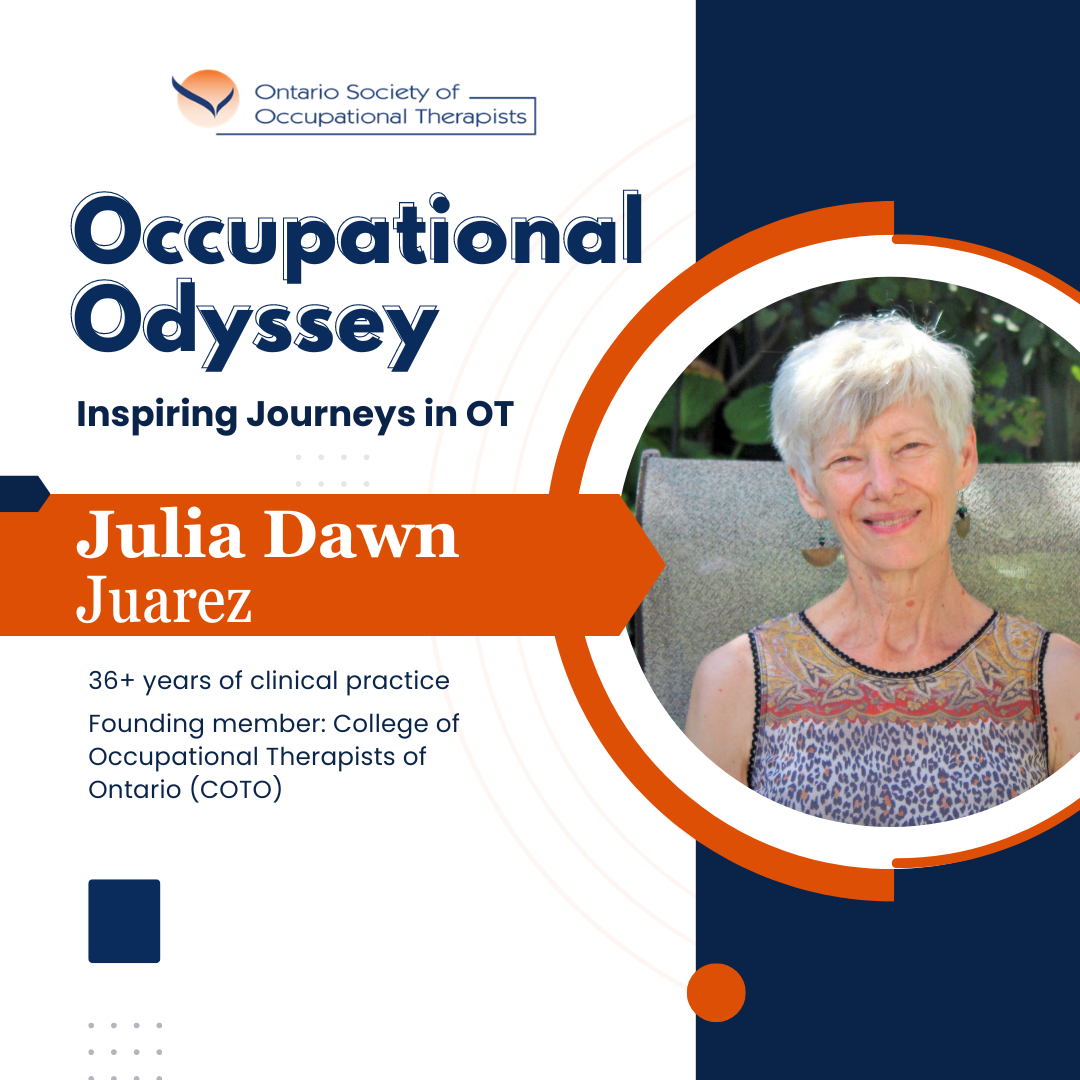

Julia Dawn Juarez

I joined the University of Alberta Occupational Therapy program in 1985 with a small group of 30 students. We were the first class to double in size and to graduate with a master's degree. Upon graduating in 1988, I was hired by the Hamilton Psychiatric Hospital. At that time, the hospital was divided into regions and conditions. I worked at the downtown "Acute" unit, half of which was locked due to the severity of the patient's condition. I learned a lot about assessing acute psychosis, cognitive assessments, de-escalating situations, and defense training. The on-ward programs developed the patient's tolerance to focus and participate in social situations, follow instructions, and differentiate reality from psychosis. Once capable, the patient could be transferred to off-unit programs. There were various programs including art, carpentry, and jobs supported by staff who negotiated and placed patients in community jobs.

A year later, I was invited to take a position in a satellite program which supported patients who had moved into the community and living in Lodging Homes. These people were stable, but quite fearful of leaving their "hospital home" that they had become so familiar with. I worked alongside an occupational therapist who had trained in England and had multiple years of experience. She talked about changes in the system that she had witnessed throughout her career. She told me that the hospital she had worked at had staff and patients farm food for the entire hospital. Patients had jobs, responsibilities, and a sense of participation. However, as the union came in, they suggested the employees have the jobs and so all the patients were relieved of their duties. With many stable people living in the hospital, it was decided to transfer them to community living.

Times were changing, my cohort retired and I was asked to be a sole-charge therapist. This required that I develop an accredited occupational therapy program. It was a great experience, as I could see the limitations of my policies and I could revise them in the annual review. I was invited by the university, along with other occupational therapy managers to develop what later became the College of Occupational Therapists of Ontario (COTO).

I moved on to a job in the community doing home care. The work was organized by districts to ease our travel distances and later transitioned into a per-visit pay schedule with an at-home office. I continued in this work for another 12 years. During this period, I was invited to do an assignment to assess the city's housing inventory for wheelchair accessibility. I filled in several leaves of absence in psychiatric and physical hospitals. In addition, I did several stints providing motor vehicle accident and worksite assessments. I eventually stepped into the role of an independent Assistive Devices Program assessor providing mobility devices.

Occupational Therapy has been a wonderful career for me, providing support and encouragement to those in need. We need to defend and support those in need, whether their issues are mental or physical. We work with people and know firsthand what their issues are. Because of political and financial pressures, their needs may be manipulated to fit the present-day narrative. Our voice, with a client-centered perspective, is necessary. OSOT is our support system. They are aware of the financial and political pressures on occupational therapy as a whole and our purpose to support the people with whom we work, whether direct client care or enabling occupational therapy professionals to provide the best services in the industry. We are recognized for our efficient and effective services enabling clients to succeed in self-empowerment.